I am weary of the pandemic (what a shock!). In addition to the obvious restrictions it has imposed I have been seriously constrained from my usual photographic practice -- wandering the streets, the sidewalk markets, the music and art festivals.

I have spent a great deal of time combing through my 35000 or so negatives looking for ones that I did not (or could not) print when they were new. I added perhaps 100 prints to my metaproject "Spying on a Memory". But now I've done that.

I have wandered the mostly empty streets in my neighborhood looking for "pandemic" pictures and I've found a few. But my heart isn't in it.

One of my favorite photographers, Frank Horvat, did a series of photographs taken no more than 60 meters from his front door showing the dreary winter around his home. (In my opinion he hedged his bet pretty seriously since he lived in an over 100 year old stone house in Provence.) I tried that out but my negatives just look, well, dreary.

Poking through boxes of loose prints I found a portrait in which I consciously tried with, shall we say, modest success to duplicate the pose of Vermeer's Girl with a pearl earring. I intended this not to be a costume piece but to be "in the manner of" to help me understand the pose and the lighting.Then I found a print I made while trying to understand how Gustave Caillebotte used multiple vanishing points to make his paintings so convincingly plausible. I sure as heck didn't expect my print to look like his painting but to be "in the manner of" to understand his use of perspective. This is a composite of two negatives -- one looking down the street on the left and the other looking down the street on the right. It is more "real" looking than a print made from a single negative looking at the corner of the building.

Norman Lundin is a Seattle painter who had a show at the Kucera gallery a couple of years ago. His paintings knocked my socks off and the gallery manager was kind enough to give me a copy of the show catalog. Lundin does landscapes -- unpopulated and often slightly spooky, even just a tad surreal. He also does interiors -- simple arrangements of items found in his studio.

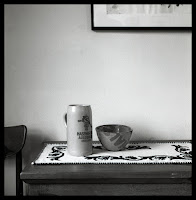

Again, not to try to look like his paintings but "in the manner of" I did a couple of still life photographs (the first such in many a year -- I even had the camera on a tripod). Neither of them look anything like a Lundin painting but they do seem to me be "in the manner of".

I just finished studying ("reading" is not an intense enough term) Andrew Wyeth -- retrospective. His iconic works are spectacular but I find his portraits even more so. Hmmm. Portraits are not very practical right now. How about how he used the winter light of Chadd's Ford to illuminate an interior?

Part of the training of an easel painter is copying master works both to hone their skill with brush and palette and to solidify in their bones how the masters used light and composition to make their works sing. I have often wondered why the training of a photographer does not include "copying" master works. Well, "copying" isn't exactly practical but perhaps "in the manner of" is. We have a north-facing window so there is raking light in the morning -- similar to that of Wyeth's Overflow.

I'm by no means sure where this is going (if anywhere) but I do seem to be learning from them and perhaps it can keep me busy for a while.